Shifting Sands by Ysella Sims

In the fields behind my house I notice a stonechat and a blackbird perched on stems in the hedgerow, missed by the flail. They are listening to the warnings and shouts of other birds, newly arrived, staking out their territory.

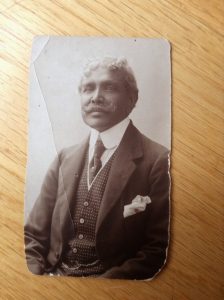

All of the world’s ills would be cured if everybody just kept to their own village, my Grandfather, Victor, a second generation immigrant, used to say. Victor, his hair parted and smoothed, his brown skin carefully shaved and smelling of sandalwood, his kind hands manicured; Victor, who always wore a suit, even for gardening.

I wonder what that saying really meant to him, and who said it first? He was a father who warned of snakes in the bracken, who held his daughter’s hand so tightly that, even now, she feels his hand in hers. What does it mean to belong to a place and to leave it, to be new and finding your place, feeling that you don’t belong?

If the land loves you, you’ll stay but if it doesn’t you’ll soon be on your way, a friend tells me when I move to a valley ribboned by the river Creedy, where the soil is stained red with iron and dashed with sandstone. A place that makes me think of the red clay of creation myths, of new identities, shapes and stories forged from the earth. A place where I begin to imagine my own rebirth, my own starting again, thinking of the people who went before but weren’t allowed to stay.

My head is full of Victor and his father Sandosham after days of trying to unpick their stories and the ways they found to fit in the world. In a dusty box of thin letters in tiny inked handwriting with postmarks from 100 years ago I find the beginnings of a family tree, a stab in the dark, the rough draft of a map amongst so much ephemera, like trying to catch sand on the wind.

*

Sandosham

Family folklore has it that my maternal great grandfather, Sandosham, worked on a tea plantation in Ceylon and was chosen to travel to England with Prince Rupert’s court for the Great Exhibition. But the dates don’t stack up, and I don’t think that Prince Rupert ever existed. Sandosham was a raconteur, a storyteller who lived on his wits, none of us know the truth of him. I imagine him on the plantation, bent double in the sun, oils from the tea plants staining his fingers, dreaming of escaping the land in the same way that I have always dreamed of returning to it.

Born in Sawyerpuram, Tamil Nadu, South India in 1866, he was named for the sandy region, in the rainshadow of the Western Ghats, that his people belonged to. I think of the greensand of my birth home, the redsand of the home I have made in Devon.

Red sand and green sand, who’ll buy my red sand, who’ll buy my green sand?

Sand is in our familial shoes.

Sandosham’s family name, Nadar, belongs to a Tamil caste of landowners and cultivators – the working classes of the Shudras Varna. I think of his family teasing life from the sticky soil – expanding and shrinking with the monsoon rains – in the same way that he teases a new life from trickery tales. He is a boy belonging to the black cotton soil, telling the world that he’s a prince and daring it to disbelieve him. Sandosham is as vivid as the village he has left behind, as changeable as its divine-willed skies, as fluid as the cyclones battering the coromandel coast, scattering salt and sand, their thunderous rains disappearing his family’s imprint on the land – the village’s rice stores, its sloping roofs and courtyards. He will escape colonialism’s surveillance and its sanctity-stripping of the land.

Like us, he is made of the stories he tells about himself.

He is a schoolboy walking a dusty village track with his cousins, a tame mongoose on his shoulder, a schoolboy failing to outrun the merciless cane of the missionary’s good works; a schoolboy who is kind to dogs and foxes, who sees the sparkle in the granite where the cobra sleeps, who watches sunbirds hovering in the ochre afternoon’s heat waver.

He is a runaway, picking tea for an Englishman and plucked – an artefact of empire – for Queen Victoria’s jubilee, thinking: But she’s such a little thing. He is a shapeshifter with a smattering of English who begs the plantation owner not to return him to India and indenture, to unbind him instead from the yoke of land and caste.

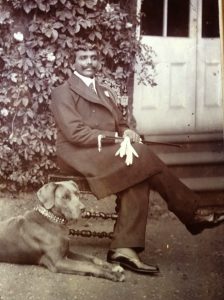

He is a lover, drinker and gambler, setting out, in the uniform of an Edwardian gentleman, for the States, saying, I am going to see America!, experiencing racism he can never bring himself to tell about, writing, draw a curtain over it. Ask me not, to his cousin on his return.

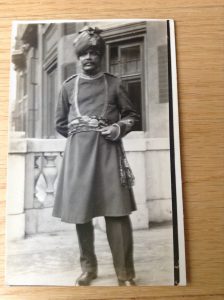

He is an exhibit at the entrance to a grand house wearing epaulettes, a tasselled sash and feathered thalappa, his shoes polished, looking like a tourist gimmick. He is a merchant attending houseparties on the Thames, taking tea with a Maori queen and the Maharaja Gaekwad of Baroda. Or he is a hotel manager, a waiter, hiding Mr Harris with the dirty ginger moustache behind the curtain until he sobers up.

He’s an old man bound by blindness in a Chelsea flat, drowning his disappointments; visited by snatches of colour – the pink and yellow of Sawyerpuram houses – by the smell of tamarind and hot oil, kerosene and banana flower, of the sea on a bright morning; by the feeling of hot sand under his feet and the sound of fishermen’s voices, the calls of peacocks and bulbuls.

As he dies he speaks German so that even in death he keeps his secrets.

It is an old, old world that has passed away, writes his cousin afterwards, it is an end but also a beginning.

The more I hold of him, the less I know.

*

Amongst the letters and documents I find his parents’ names. I hold them up to the light like coloured glass, turning them over on my tongue, self conscious, careful with their syllables;

Veth-a-man-ikam, Veth-a-man-ikam, Patik-iam, Patik-iam.

I wonder what they would sound like on Sandosham’s tongue, on Victor’s?

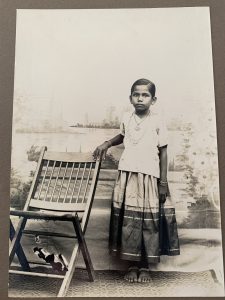

In photos sent from India, from Sandosham’s relatives, are people who appear to be Tamil Brahmins, rather than farmers. Here is a photo of a girl in a full silk skirt and a blouse, wearing silver belled anklets, necklaces and bangles, her feet bare. I look up the Tamil names for her clothes and jewellery, sounding them out like an incantation, trying to make them mine, knowing that they will never be and wondering at my sense of longing, of loss:

Ravikai, Choli, Pudavai,

Veshti, Angavastram, Jibba,

Pavadai, Thodu, Malai

Here is a photo of a couple telling their own story; she in a shining saree and jewellery, he in a three piece suit and a fob chain, a backdrop of a pillared and carpeted gothic mansion, a fern in a china planter, stage left. And here is a photo of a tense family on a tiger skin; a child hiding beside his mother, she looking nully at the camera. The man, in a formal bandhgala coat and holding a stick, his thalappa on the floor at his feet, has placed his hand on the back of his wife’s chair, telling us he’s in command.

There are clues in each of these photos, taken in Tuticorin, now Thoothukudi, a Tamil Nadu port, famous for pearl fishing and shipping – and as a place of resistance to British colonial rule. In a country still reckoning with its imperial past, where migration stories can be politicised or erased, I’m curious to dig into the liminal spaces, the quiet places, where memory and land meet, wondering if we belong to people or place, how much agency we have in a world shaped by exploitation to stay where we feel we belong or to move beyond ourselves and the space set out for us?

The sands are shifting.

*

Lilly

Here now are photos of brown-skinned Sandosham with his white-skinned wife Lilly, a Norfolk maid he met at a house party, in Edwardian dress on a London park bench. Their legs are crossed – his towards her, hers away from him, their hands folded on their laps. He has taken his coat off because the sun is shining. He is silver haired, assured, his starched white collar glowing. She is wearing a big black hat like a housemaid on her day off.

What did London make of them? What did her family think of him, of them?

Here is Lilly again, in Edwardian lace and pearls holding a brown-faced baby with a startle of thick black hair. Here is a photo of the baby, Victor, a boy now, in a white silk suit in an Edwardian parlour, holding a violin under his chin and wearing an air of make-believe and forced happy-ever-after. Here is a photo of Victor holding his Norfolk cousin’s hand, a kind faced girl dressed like a doll, like his life depends upon it.

How did Lilly feel to leave behind Norfolk for service in London, to be parted from her siblings, scattered to the killing fields of the Somme, to London, to America in search of work?

Lilly is modest and level like the landscape she was born to. She knows the harshness of cheating northeasterlies, how rawness settles into knuckles and cheeks, but she is steady like the nearby waterways – reeded and secret. She feels the possibilities of the skies, the way that the vast space pushes them together. The land makes her hungry for closeness, for more, for ease. Her levity anchors her when taunts and cruelties catch her in the Chelsea streets.

Each summer Lilly takes Victor back, from the cramped flat in Chelsea, where Victor plays alone and his toys must be tidied away, just so, to Dereham in Norfolk. She takes him back to the place she belongs, to its feeling of flatness and open space, its cow-parsley ditches, shallow valleys and pockets of copse, back to its hawthorn hedgerows hopped by wrens, to its smell of meadowsweet and wet clay. She takes him home to her people, farm labourers nestled in cottages like kittens in haystacks; back to a cottage where they eat potatoes and green beans – cold on Sundays – and baby rabbits, sliced in half and fried. Back to a place where the cupboards are full of homemade jam, and George eats plump for breakfast in a dustmoted kitchen.

At Liverpool St. Station Sandosham buys the porter a drink and Lilly and Victor climb into a carriage, glad to be leaving London behind, its urgency and chemical air, its tight alleys where Victor is pinned, its smell of kerosene and empire. They eat the egg sandwiches Lilly has packed, watching the soot-darkened terraces peel slowly into green. They look for the white of Emily’s handkerchief across the fields, waving from the cottage the same way that Victor will one day wave to us, as if we’re setting sail on a journey from which we might never return.

From Dereham station they take the horsebus up the lane, over the bridge, around the bend until Emily and George, hearing the horse’s feet, the carriage’s solid wheels on the gravel, go out with the cousins to greet them. The children fall quickly to playing horses in the lanes, to fetching milk from Mrs Grey in the mornings, to looking for the baker’s square cart to beg a ride to Shipton, to playing in the dust and nettles, to watching the rise and fall of skylarks above the fields.

At the end of the summer, everybody cries waiting for the horsebus to take Lilly and Victor away.

*

Ysella

I am melancholy for the place I left behind the way that I imagine Lilly was, the way that I imagine Sandsham might be if his grief and anger could pass. I am melancholy like the shaded woodland, the pine tree dark, the broadleaf mulch and huddle of the greensand ridge, the place where I belong. I am acidic like the hot sand on the heath, thunderous like May’s purple skies, the tang of bracken, green and sharp. I am light like the white chalkland of the north downs, their meadows of scabious danced by chalkhill blues and bees. I am the smell of the wild marjoram’s crush, the sound of the cuckoo on the heath, the seductive shade of the towering pines on the hill, foxgloves in their glades, the bright flare of gorse on the horizon. I am soft like the seven sister hills, changeable like the weather slipping and roiling between them. I am insistent and urgent like the traffic’s roar.

But I have left this place, restless, wandering; finding in Devon a house with the same silence as the one inside me, and a garden that makes me giddy. A garden that connects me to that place with bluebells and cow parsley, that whispers to me, lie down, press your back against the earth, you have come home.

I have found a place, a landscape and a community which asks – are you ready, are you able to stay?

Would Lilly, would Sandosham, if given a choice – given the chance again – have stayed?

***

Ysella Sims is a writer, poet and performer whose work explores identity, belonging and our connection to place. Based in the rural South West, she writes from the edges, seeking connection in the in-between. Read more on her Substack.

All photographs are courtesy of the author’s collection.